Black Razorback Fans of the Jim Crow Era: A Forgotten Past

Posted: May 13, 2015 Filed under: College Football, High School Football | Tags: Darrell Brown, first black fans, Jerry Hogan, Orville Henry, War Memorial Stadium history 1 CommentThe history of the African-American athlete at the University of Arkansas has become well chronicled in the last couple decades. Many outlets have covered their experiences on the field – ranging from Yahoo sports columnist Dan Wetzel’s look at Darrell Brown, the first black Razorback football player, to a new “Arkansas African American Sports Center” business which focuses on the histories of black student-athletes at the UA across various sports. The university’s athletic department itself has created a series honoring its minority and women trailblazers.

But what about the history of the Razorbacks’ black fans?

That story appears to be entirely unreported. It’s time that changes and – thanks to Henry Childress, Sr. and Wadie Moore, Jr. – the right time is now.

Childress, Sr., likely the oldest living African-American man in Fayetteville, told me about a small group of black men, women and children who consistently attended Razorback football games at Razorback Stadium in the 1940s. Remember – this was an era in which Jim Crow laws still pervaded the South, although the social climes of Fayetteville have always more progressive than many other Southern towns (aside from a brief flare-up of KKK activity in the early 1900s).

Childress, Sr., now in his upper 80s, recalls seeing about 25-40 black Hog fans at games he attended in the 1940s through early 1950s. They weren’t allowed to sit in the bleachers like all the white fans. Instead, they had to sit in chairs on the track which then encircled the football field. But black and white fans alike Woo-pig-sooed their hearts out during the games against Tulsa, Texas, Texas A&M and SMU which Childress, Sr. saw. A black Fayettevillian named Dave Dart was the loudest cheerleader. “He’d be out there – he’d be out on the side of the field almost. He’d be just a-holerrin’ and yelling ‘Come on!'” And soon enough, Childress couldn’t help but join the frenzy.

This Hog mania was a far cry from Childress’ younger days growing up in Ft. Smith. Then, he didn’t consider himself a Razorback or much of a football fan at all. One reason was Hogs’ games didn’t then dominate statewide airwaves like they would after 1951, when Bob Cheyne – the UA’s first publicity director – crisscrossed the state to enlist 34 radio stations in the broadcasting of Hog games.

Plus, Childress hadn’t gotten swept up in football mania at his all-black Ft. Smith high school. Lincoln High had cut its football and baseball programs by the time he moved to Fayetteville in 1944, he recalled. He added in the early 1940s the school only sponsored basketball. The teens who still yearned for football simply gathered to play it by themselves on a nearby field after classes let out. “We’d go out to the back of the school, and choose up sides.”

After moving to Fayetteville, it took a little while to warm to the fanaticism and voluminous qualities of certain Razorback fans. “It was kind of strange to me,” Childress said. “I just came out and sat and looked.” Pretty soon, though, he got the hang of it. He learned many fellow black fans actually worked on the UA campus, usually as part of house, cafeteria or groundskeeping staff. This meant they personally knew the white student-athletes for whom they rooted. Dave Dart, for instance, worked at a fraternity home and cheered on the frat bro-hogs he knew by name, Childress recalled.

Hog games weren’t the only setting where black Fayettevillians came to cheer all-white spectacles. Childress said in this era both races got off work to watch the town’s parades (which then featured all-white floats). “We’d come out and stand. There would be lines all up and down Dickson Street.”

I asked Childress what he then thought of the whole situation. Did he or any friends at any point consider it unfair only white players could represent a state university to which blacks had contributed as employees, taxpayers and students since its 1872 founding?

“No, we didn’t give it a thought,” Childress said. “Wasn’t nobody [African-American] going over there to school,” and he didn’t expect an influx of black UA students to begin any time soon.

What About Black Fans at War Memorial Stadium?

I haven’t yet found anybody who can speak to the experience of central Arkansan blacks at Razorback football games at Little Rock’s War Memorial Stadium in the immediate years after its 1947 construction.

But I did find Wadie Moore, Jr., who recalls the situation in the early 1960s Little Rock was more stratified than in 1940s Fayetteville. As a 13-year-old in 1963, Moore began working at War Memorial, where his father was a maintenance worker in the press box. Moore said about 5-10 black fans would attend each Little Rock Razorback game in that time. They didn’t sit in sight of the white fans. Instead, stadium policy “would allow you to sit under the bleachers in the north end zone and watch the game,” he said.

Wade Moore Sr.’s proximity to the media – including future local legends like Jim Bailey, Bud Campbell and Jim Elders – actually opened doors for his son, though. When Moore Jr. found a passion for sportswriting as a high schooler at Horace Mann High School, it was his father who made sure an article he wrote got into the hands of Orville Henry, the longtime sports editor of the Arkansas Gazette.

The mid to late 1960s brought a tidal wave of change to racial dynamics across the South and War Memorial was no exception. Wadie Jr. recalls one of first times he saw black Razorback fans sitting in the crowd – and not secluded below in the stands – coincided with the Little Rock homecoming of one of the Razorbacks’ first black band members. The young woman’s family, last name of “Hill” as he recalled, watched her in the audience around 1965 (the first year black UA students were allowed to live on campus) or 1966. In 1965, too, a young walk on named Darrell Brown joined the defending national champions in Fayetteville full of hope he could break down regional color barriers all by himself. By the end of the next fall he would limp away, that hope beaten out of him.

But he had opened the doors for others, including Jon Richardson – who a few years later became the Hogs’ first black scholarship player.

In 1968 one of Richardson’s schoolmates, Wadie Moore, Jr. became the first black sportswriter at Arkansas’ oldest and most prestigious statewide newspaper.

There are hundreds of other stories about Arkansas’ forgotten sports heritage which need to be recorded and published before it’s too late. Thank you to Henry Childress, Jr., Rita Childress, Jerry Hogan (author of the NWA pro baseball history Angels in the Ozarks) and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History) for helping me find a treasure of historical knowledge in Henry Childress, Sr. Send tips on stories/interviewees to evindemirel [at] gmail.com.

For more on this topic, visit my other work here:

1. Vanishing Act: What Happened to Black Baseball in Arkansas? (via Arkansas Democrat-Gazette)

2. Integrate the Record Books (via Slate)

3. It’s Time Arkansas Follows Texas in Honoring its Black Sports Heritage (via The Sports Seer)

Brad Bolding’s Lawyer Hints At Deeper Problems for NLRHS Athletics

Posted: February 8, 2015 Filed under: College Football, High School Football | Tags: Brad Bolding, KJ Hill, North Little Rock, Urban Meyer 1 CommentGood stuff from Sports Talk with Bo Mattingly on the latest concerning the K.J. Hill/Brad Bolding/Potentially A Whole Lot More controversy smoking in North Little Rock right now. The fallout has been swift and deep – head football coach Bolding dismissed, North Little Rock High forfeiting its 2014 state basketball title and now K.J. Hill’s amateur status in doubt.

Much of the issue traces back to a $600 check K.J. Hill’s stepfather Montez Peterson was given in February 2013. Peterson was then a NLR football team volunteer while Hill had not yet transferred from Bryant to NLRHS (that would happen two months later).

Was this illegal recruiting? Despite Peterson’s adamant denial, some believe that check confirm Hill’s move to NLR (which Peterson said was inevitable at that point anyway). And was Hill even living in a NLRHS district zone? This, and more, were things Mattingly brought up in an interview with Brad Bolding’s attorney David Couch on Friday.

Here’s an excerpt from their talk:

Couch: [Hill’s] family rented a house when they first moved here, it was in the district. Subsequently, they begun to rent an apartment that wasn’t in the district and when they found out that that apartment was not in the district, they changed it and they moved to another house that was in the district. So he was in the district.

Mattingly: So he started in the district, went out of the district, became aware of it, moved back in the district?

Right. And am not sure that the second part of that is that he actually went out of the district. I know they rented an apartment I don’t know if they took possession of it or for how long they did.

We are talking to Brad Bolding’s attorney David Couch our guest here on the JJ’s Grill Hotline. Lot of rumours, stuff like you know there was an apartment paid for by Bolding by Foundation money for KJ Hill and his family to be able to live in. What will Brad Bolding say when it’s his opportunity to talk about those kinds of accusations and I know you are hearing?

I can tell you right now that those are absolutely untrue. I mean I have, ah – there’s no evidence to that at all. I’ve looked at all of the NLR Foundation bank statements and accounts as has the North Little Rock School District. That’s just – it simply not true. And it is not even alleged by North Little Rock as something we should be even talking about.

Yeah. Ok. But what is it that you are going to say, or coach Bolding is going to say when you have your day. You are going to have a hearing, right? To appeal this?

Yes sir. Right.

OK. When you are there, what are you going to say in regards to why you think that North Little Rock school district has laid out this case that in your mind is – I don’t want to put words in your mouth – but, not reasonable for his firing. What, why do you think they are doing this?

You know, anytime you have an organisation I think have a clash of personalities. I think that has something to do with it and then one of the things I think will come out and am going to say it now is that sometime in the late fall, Coach Bolding started inquiring about invoices from the athletics department that had not been paid and not been paid and still may not be paid. And you know, there is some grant money that the athletic department got from the state that may or may not have been used in the correct way. So when [he started] asking those kind of questions coincidently you know, is when these problems started arising.

Listen to the rest of the interview here.

The Pine Bluff Native Whose Protest Rocked the College Football World: Part 2

Posted: January 15, 2015 Filed under: College Football, Sports Sears | Tags: Black 14, Ivie Moore, Joe Williams, Jonathan Williams, Tommy Tucker, Tony McGee, Wyoming football 1 CommentBelow is the second act of my two-part series on Ivie Moore, an Arkansan sports pioneer who should be remembered.

It cost all of them.

Eaton didn’t sympathize. Indeed, his reaction was the opposite of what the players hoped for, Hamilton recalled in a wyohistory.org interview:

“He took us to the bleachers in the Field House and sat us down, and the first word out of his mouth was, ‘Gentlemen, you are no longer on the football team.’ And then he started ranting and raving about taking us away from welfare, taking us off the streets, putting food in our mouths. If we want to do what we want to do, we could [go] to the Grambling [College] and the Bishop [College], which are primarily black schools, historically black schools.

And so he–he just berated us. Tore us down from top to bottom in a racial manner.”

The players emptied their lockers that same day. They requested a future meeting with Eaton along with school administrators, but Eaton didn’t show up. In the ensuing weeks, Laramie became the epicenter of a national civil rights debate involving students’ rights, the power of the athletic department and free expression.

“As the student and faculty groups sought to challenge the dismissals, the demise of the Black athletes began to garner support around the WAC and around the country. The success of the football team and program guaranteed national exposure, evidenced by the arrival in Laramie of ABC, CBS, and NBC film crews,” Clifford Bullock wrote in a scholarly article for the University of Wyoming.

“On October 23, 1969, President Carlson and Coach Eaton held a press conference and announced an immediate change in Eaton’s rule regarding protests. This policy change would not affect, however, the Blacks already dismissed. It was at this press conference that Sports Illustrated reported that President Carlson admitted that at Wyoming, football was more important than civil rights.”

The Pine Bluff Native Whose Protest Rocked the College Football World: Part 1

Posted: January 13, 2015 Filed under: College Football, Sports Sears | Tags: Black 14, Ivie Moore, Pine Bluff, Razorback Jonathan Williams, sports protests, Wyoming football 3 CommentsIvie Moore will likely never meet Razorback Jonathan Williams. It appears Moore has hit some serious hard times down in the Pine Bluff area. For Williams, four decades younger, life in Fayetteville is ascendant. The All-SEC running back helped power one of the strongest Arkansas season finishes in decades and come August will headline a dark horse contender for the SEC West crown. God willing, he’ll be training for the NFL this time next year.

While the lives of Moore and Williams have little in common these days, they did intersect once. As college football players, both took brief turns in the spotlight as supporting characters in a much larger drama involving social movements sweeping the nation. Williams’ moment happened just a few weeks ago, with a “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” gesture captured on national television. Moore’s time came more than 45 years before, as one of the “Black 14” whose legacy is cemented in Laramie, Wyoming…

The late 1960s were a time a massive social upheaval in the United States. The Vietnam War and Beatles were at full blast, and in the span of three months in 1968 political icons Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. Young Americans openly rebelled against authoritarian figures for a variety of reasons and sports presented no sanctuary from the winds of change. Basketball, track and football student-athletes participated in protests against racial injustices and Vietnams across the United States.

In October, 1969, one of the sports world’s most significant political protests sent tremors through the University of Wyoming, where Pine Bluff native Ivie Moore was starting at defensive back. Moore, a junior, had transferred from a Kansas community college and was part of a perennial WAC championship program that had in recent years beaten Florida State in the Sun Bowl and barely lost to LSU in the Sugar Bowl. In 1969, Wyoming got out to a 4-0 start, rose to No. 12 in the nation and was primed to pull off the most successful season in school history.

It never happened. Not after Mel Hamilton, one of the school’s 14 black players, learned about an upcoming Black Student Alliance protest in advance of an upcoming home game* against BYU. The year before, in Wyoming’s victory at BYU, some of the black players said the Cougars players taunted them with racial epithets, according to a 2009 Denver Post article. “The Wyoming players had also learned that the Mormon Church, which BYU represents, did not allow African-Americans in the priesthood.” Hamilton, Moore and the other 12 black players wanted to show support for the protest by wearing black armbands.

Their militaristic head coach, Lloyd Eaton, had reminded them of a team rule forbidding factions within the team and participation in protests. The black players met and decided it would be best if as a group they met with their coach to discuss what they felt was a matter of conscience. On October, 18, the day before the BYU game, they dressed in street clothes and walked to his office wearing the black armbands they had been considering for the game. “We just wanted to discuss this in an intelligent manner,” “Black 14” member Joe Williams recounted in the Laramie Boomerang. “We wanted to play this game no matter what. We hadn’t even decided to ask permission to wear the armbands during the game.”

“It kind of scared me at first because I knew every one of the Black 14 could have played pro. I knew if we stood up it could damage our careers,” Ivie Moore said in Black 14: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of Wyoming Football. “But I knew that at some point in time you’ve got to stand up for what you believe in.”

“And after thinking about it, I stood up.”

Click here for the second half of this story.

Arkansas State’s Coaching Carousel of Success Not So Historic?

Posted: December 26, 2014 Filed under: Non-Razorback football in Arkansas, Razorback football | Tags: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette 2014 Sportsmen of the Year, Arkansas State seniors, Blake Anderson, Frankie Jackson, Hugo Bezdek, Larry Lacewell, Qushaun Lee, Sterling Young Leave a commentMega kudos to Arkansas Democrat-Gazette for naming @RedWolvesFBall 10 5th year seniors its Sportsmen of the Year! pic.twitter.com/V3SJBt3INp

— AStateNation (@AStateNation) December 25, 2014

Arkansas State fans often feel slighted by media in central Arkansas (despite KATV sports anchor Steve Sullivan’s strong ASU ties as an alum), but reasons for that chip on the shoulder are dwindling. On Christmas Day, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette made an unusual move in naming not one – but 10 individuals – as its “Sportsmen of the Year.” More unusual was the fact the sportsmen weren’t associated with the University of Arkansas.

Reporter Troy Schulte did a good job writing the piece [$$], and he got some interesting insight from ASU linebacker Frankie Jackson, one of the ten fifth-year seniors who persevered despite going through the tumult of five head coaches in five years. “No matter what came in, it was still, turn to your left, turn to your right and you still have the same players you knew from your freshman year,” Jackson said of his classmates from the 2010 signing class. “It wasn’t the head coach, it was the team that I wanted to be a part. It didn’t matter that Roberts left, Freeze left, or Malzahn left or Harsin left — I was still with my team.”

Those are rare words coming from a player still playing for a mid-major/major Division I football program.

Usually, football program try to sell the coach as the face of the program for obvious recruiting reasons. Putting the coach front and center as the program’s public figurehead also helps boost coaches’ show ratings and sell tickets for booster club meetings. Arkansas State’s situation is so unique, however, that the “players first” slant is the only one that works without coming off as ridiculously out of tune. That being said, it will be interesting to see if the ASU football program makes this article part of its recruiting package to its current high school and junior college targets.

On one hand, this kind of front page exposure and honor seems like something the Red Wolves would want to play up to its recruits – “Hey, look, the Hogs aren’t the only major football player in state, and Arkansas’ biggest newspaper agrees!” On the other hand, if you’re current ASU coach Blake Anderson, what do you do say in response to Jackson’s words here –

“It wasn’t the head coach, it was the team that I wanted to be a part.”

Anderson’s got much bigger things to worry about, of course. He’s leading ASU into the GoDaddy Bowl on Jan. 4 in Mobile, Ala., where it hopes to pick up its third consecutive bowl win. This would cap the fourth consecutive winning season for the ASU, a major accomplishment considering from 1992 to 2010 the program had endured 16 losing seasons.

For the Red Wolves, annual coaching turnover has gone hand and hand with consistent winning since Hugh Freeze took over for Steve Roberts in December 2010. Schulte points out that in the last 100 years this unusual combination is unprecedented: “The only other known team to go through such change at the sport’s highest division was Kansas State in 1944-1948, but those teams won just four games through that transition.”

Going back farther in time, though, there is one program that likely comes closest to replicating ASU’s combination of high success and high coaching turnover.

From 1895 to 1906, Oregon had 10 winning seasons and two undefeated ones. Still, the Webfoots went through nine coaching changes in that span. Granted, college football coaching was then approximately 6.5 million times less lucrative in that era, so the young men who so often became coaches immediately after their playing college careers sometimes jumped ship simply to pursue a career in which they could make serious money.

Take Hugo Bezdek, who led Oregon to a 5-0-1 record in 1906, his only season there. Instead of returning, though, he returned to his alma mater the University of Chicago to pursue medical school. Still, nobody forgot the Prague native’s prowess. “Bezdek is by nature imbued with a sort of Slavic pessimism that makes him a coach par excellence,” according to a 1916 Oregon Daily Journal article. “His success lies in his ability to put the fight into his men.”

Someone at the University of Arkansas heard about Bezdek’s ability and reached out to the 24-year-old to offer a position as the football, track and baseball coach (Oh, and entire athletic directorship, while he was at it). Bezdek arrived in Fayetteville in 1908 and a year later his team went undefeated (7-0-0), winning the unofficial championships of the South and Southwest. In 1910, the team was 7-1-0. Impressed with the mean-tempered hogs that roamed the state, Bezdek observed that his boys “played like a band of wild Razorbacks” after coming home from a game against LSU. The new name caught on, and in 1914 the Cardinals officially became the Razorbacks.

The Red Wolf Ten

Below are the ten 5th year seniors who have ASU on the cusp of 36 wins – what would be its second-most successful four-year run ever. “It’s a miracle on a cotton patch up here,” former coach Larry Lacewell told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Lacewell, ASU’s all-time winningest coach, led the program to its best four-year run of 37 victories in 1984-1987. Lace well said these seniors “brought tradition and pride back to Arkansas State.”

1. Brock Barnhill; DB; Mountain Home; Former walk-on; special teams contributor

2. William Boyd; WR; Cave City; Walk-on earned scholarship. Caught first career pass this season

3. Tyler Greve; C; Jonesboro; Started 12 games at center this season

4. Frankie Jackson; DB; Baton Rouge; Played RB and LB (917 career yards, 65 career tackles)

5. Ryan Jacobs; DB; Evans, Ga.; Played mostly on special teams; 11 tackles, 1 fumble recovery

6. Qushaun Lee; MLB; Prattville, Ala.; Fourth all-time on ASU’s career tackles list (390)

7. Kenneth Rains; TE; Hot Springs;7 starts; 14-160 receiving, 3 TDs

8. Andrew Tryon; SS; Russellville; 24 starts; 149 tackles, 20 breakups, 3 INTs;

9. Alan Wright; RG; Cave City; 21 starts

10. Sterling Young; FS; Hoover, Ala.; 45 consecutive starts: 268 tackles, 151 unassisted; 7-59 INTs

NB: Defensive tackle Markel Owens also would have been a fifth-year senior this season. He was shot and killed at his mother’s home in Jackson, Tenn., in January, 2014.

Above information taken from Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and ASU athletic department.

New Study: Missouri Only SEC Program Hating Arkansas More than Other Way Around

Posted: November 28, 2014 Filed under: College Football, Razorback football, SEC Football | Tags: Arkansas Razorbacks, Arkansas State, Battle Line Rivalry, David Tyler, Joe Cobbs, Missouri Tigers Leave a commentThe meaning of “rivalry” and whether it can already be applied to Missouri-Arkansas has been much debated this week. Although today’s game marks only the sixth time the programs have ever met, it appears both sides are comfortable with the notion of a bona fide border feud. “Arkansas – they have the word ‘Kansas’ in it, so it’s got to be a rival,” Missouri center Evan Boehm told media a few days ago, referencing his program’s top rival during its Big 12 days. Tigers head coach Gary Pinkel added: “It will be [a rivalry]. I kind of compare it to the Kansas rivalry. It didn’t happen overnight.”

The potential for a real, intense and disturbingly partisan rivalry is here, alright. Today, Missouri has an SEC East title and second straight appearance in the SEC Championship Game on the line. And Arkansas is arguably the nation’s hottest team after shutting out LSU and Ole Miss. A win sends it roaring into bowl season as a Top 25 program.

From a numbers standpoint, though, what would such an “authentic” rivalry look like and how close is Mizzou-Arkansas to it? We have actual data along these lines thanks to Dr. David Tyler and Dr. Joe Cobbs, two professors who have studied the perception of rivalry* among 5, 317 fans of 122 different major college programs. Here are two of their most interesting finds:

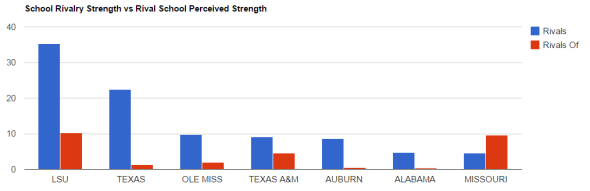

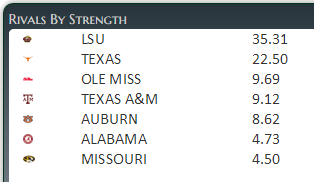

1) Arkansas’ fans, on the whole, feel that they are rival to other programs more than the other way around. The blue columns below signify, through points, the strength of Arkansas’ fans’ passion directed toward a particular program. The red columns represent how many “rivalry points” that program’s fans have for Arkansas.

You’ll notice among SEC programs only Missouri fans believe Arkansas is a bigger rival than visa versa:

LSU’s ranking shows that the Texas Longhorns’ grip on Arkansas’ fans hearts is slowly loosening 22 years after the Hogs left the Southwestern Conference. No one program has yet filled the void. “This is a pretty big distribution of [rivalry] points by a fan base,” researcher David Tyler told me. “The average points received by a team’s top rival is 54.2 points (median & mode are right around there too), so the 35 points that Razorback fans give to LSU is on the low end.”

[*The researchers assigned “Rivalry points” after collecting data from online questionnaires they posted on 194 fan message boards. The survey asked respondents to allocate 100 rivalry points across opponents of his or her favorite team. The closer the number to 100, the more intense feelings that programs’ fans have for their perceived top rival. Missouri, for instance, has 71.58 rivalry points directed at Kansas. One Tiger fan divided his 100 points, 75 to Kansas and 25 to Arkansas. “This would have been 100 points for Kansas prior to the SEC switch. Not really sure how to handle this now, but this split seems okay.” More details at KnowRivalry.com]

2. The other FBS programs perceiving Arkansas as a bigger rival than visa versa are Tulsa and Arkansas State University. Tulsa has 6.57 points toward Arkansas, though Tulsa doesn’t register at all on Arkansas fans’ radars. Arkansas State, meanwhile, has 24.7 points allocated to Arkansas, while Arkansas has .096 for A-State.

These programs, of course, don’t even play each other. Dr. Tyler points out “frequency of competition isn’t a necessary condition of perceived rivalry (at least in the eyes of some fans). Frequency of competition is an antecedent to most rivalries, but this is a great example where the teams don’t play but fans [on one side] still perceive a rivalry.”

Tyler and his colleague found “Unfairness, Geography and Competition for personnel (e.g. recruits)” as common themes among those poll respondents who listed Arkansas as their biggest rival. Below are some responses/themes from A-State fans he shared with me:

-

“We don’t play the pigs on the field, yet they have tried to keep us from growing our program since the beginning of time. They even tried to block us from gaining ‘university’ status in the late 60’s. / They want to be the only team in the state, and refuse to acknowledge our existence…all the while, playing every one of our conference mates. / I hate them, and hope they lose every game in every sport they participate in.”

-

“Arkansas refuses to play us because they are scared.”

-

“Hogs is scared to play us.”

-

ASU fans hate Arkansas fans and vice versa (Big brother keeping little brother down – UA will not play Ark St because they feel they own the state support and media and don’t want to let Ark St have any).

It should be interesting to see if A-State fans’ passion towards the UA wanes or waxes as the program continues to carve out a niche as a mid-major power. As for Missouri-Arkansas, there is no doubt both programs’ level of mutual hate permanently rises once the game kicks off at 1:30 p.m. today.

Perhaps, one day, Missouri’s fans will hate Arkansas as much as they have Kansas, and Hog fans will find in their hearts Texas-sized enmity for their neighbors to the north. It will take a few games of this magnitude before that becomes even a remote possibility. Until then, though, expect to read more fan comments like this: “Missouri is to Arkansas what Canada is to America. They’re too damn nice to hate.”

Below are detailed results from Arkansas Razorback fans’ responses, according to KnowRivalry.com

Top 50 (ish) Major College Football Rivalry Trophies: Part 1

Posted: November 28, 2014 Filed under: College Football, Sports Sears | Tags: Apple Cup, Best Trophy Games, Jefferson-Eppes, Okefenokee Oar, Platypus Trophy, Rivalry games, Territorial Cup Leave a commentHeaded to Athens! #WarfortheOar pic.twitter.com/Vpox1R1f

— Okefenokee Oar (@OkefenokeeOar) October 30, 2011

More than 60 major college football trophies are out there, just itchin’ to be broken down on a criterion-by-criterion basis and judged. Break out the metaphorical Aveeno. They need itch no more.

Below is a countdown of the Top 48 rivalry trophy game trophies, ranked in a three-part system of these factors: originality, tradition and Sheer Awesomness. See here for more details, but bottom line is that number at the far right is the total score (L-R: scores are for originality, tradition and Sheer Awesomeness)

46.

| Governor’s Cup | Kentucky-Louisville | 1994 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

By far looks the most awesome of the three rivalry series governor’s cups nationwide. But such an unoriginal premise….

(Year in italics marks first year awarded was given)

45.

| Victory Cannon | Central Michigan-Western Michigan | 2011 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

Already was a trophy w/ “victory” in its name out there. And others involving a cannon.

(PS – The scoring above works like this: originality 2

+ tradition 3

+ Sheer Awesomeness 2 = Total Score of 7 [of maximum of 15] )

44.

| Legends Trophy | Notre Dame-Stanford | 1989 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

Leave the beautiful, symbolic hybrids of Irish crystal and California redwood to the art museums.

43.

| Platypus Trophy | Oregon-Oregon State | 1959 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

Not a game trophy; goes to alumni associations instead.

42.

| Apple Cup | Washington-Washington State | 1962 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

Conceptually, this is just such low-hanging fruit, state of Washington.

41.

| Jefferson-Eppes | Florida State-Virginia | 1996 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

Elegant, yes. Awesome? No.

40. and 39. (PS: Sorry, I’m an irrational maniac with these tandem groupings. I know.)

| Governor’s Cup | Georgia-Georgia Tech | 1995 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Governor’s Cup | Kansas-Kansas State | 1969 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

Sigh. Yet another Governor’s Cup. Someone needs to legislate a limit here.

38.

| Bronze Stalk | Ball State-Northern Illinois | 2008 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

Sorry, but I’m not playing even an ounce harder for the propsect of winning a giant corn and neither should you.

Worst 15 Trophy Rivalry Games In Major College Football

Posted: November 25, 2014 Filed under: College Football, Sports Sears | Tags: Best Trophy Games, Worst Rivalry Games, Worst Trophies in college football, Worst Trophy Games 1 CommentEarlier this week, the Associated Press produced a “Best Traveling Rivalry Trophies” list that does scant justice to the ritual. Simply passing a hat between scribes and listing old-ish trophy games, one through ten, ain’t cool, AP. No description? No evaluation? Nary a mention of criteria!?

Smh.

Our nation’s great game deserves better. It deserves more. It deserves a Greg McElroy-in-SEC Network-film-room-bunker-style breakdown of each and every one of the current trophy rivalry games at the major college level along with the involved programs. Rest assured, such an arch-analysis – and master ranking – is coming soon to an SB Nation page near you.

One major aspect of the rivalry game ranking should be coolness of the trophy itself. Along these lines, I have devised a 15-point scoring system to produce a score that is actually a composite of three sub-categories: “Originality,” “Tradition” and “Sheer Awesomeness.” Each of these sub-categories is worth 0 (worst) to 5 (best) points.

“Originality” represents how unique the trophy and its name are, as well as how unique and relevant its origin story is for the students of the involved programs. Naming a trophy “Governor’s Cup” is not looked kindly on in this department. Tradition represents the extent to which the trophy has meaningful ties to the programs and/or native region, and the significance the trophy holds in the larger context of game-day rivalry rituals between the programs.

The last metric here is “Sheer Awesomeness,” which admittedly can sometimes be in an eye of the beholder type thing. But here it’s simply a blended answer to two very straight-forward questions:

1) You’re Scot warrior William Wallace, of 13th-century kicking-ass fame. You’ve been parachuted across time into modern America and before you learn what a cell phone is you’re told to fight for Trophy X. Upon first seeing it, how hard does your brave heart start beating?

2) If a group of major college football players were to win a spot on Extreme Makeover: Apartment Edition, how much would they enjoying seeing Trophy X appear in the corner of their TV room, regardless of what college they play for?

Ok, that part was easy.

Now, on to the next step: Add the point totals from all three categories together and you get my final, cumulative trophy score. It’s dubbed “Sweetness of Trophy,” or S.O.T. for short. I’ve highlighted each S.O.T. score in red below.

As of a point of reference, after the names of the programs, the categories from left to right follow as such:

Year Trophy First Awarded; Originality; Tradition; Sheer Awesomeness; Sweetness of Trophy

Let’s get on with the rankings. We’re starting at the bottom:

62.

| Textile Bowl | Clemson-North Carolina State | 1981 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Finding out this rivalry is considered by those who know it exists to be “friendly” is bad. Seeing the actual trophy – possibly the sport’s most anodyne – is worse.

61.

| Shillelagh | Purdue-Notre Dame | 1957 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

Were there an American Gaelic war club trophy club, Notre Dame would be its charter member.

60.

| Hardee’s Trophy | Clemson-South Carolina | 1999* | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

Some reports indicate the Hardee’s era is mercifully over. South Carolina’s sports department tells me it will be around for at least one more Palmetto Bowl.

59.

| The Bell | Ohio-Marshall | 1997 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

How is this not a farcically blatant rip off of nearby Miami(Ohio)-Cincinnati’s Victory Bell?

Matt Jones’ & David Bazzel’s Ideas for an Arkansas-Missouri Rivalry Trophy

Posted: November 15, 2014 Filed under: College Football, Razorback football, SEC Football | Tags: Battle Line Rivalry, Battle Line Trophy, Fantastical Zoomorphic Witches' Brew Conceptions, Matt Jones, Missouri-Arkansas Leave a commentCan Missouri become the legit Arkansas rival into which LSU never quite developed?

Many Hog fans believe so. From a geographic standpoint, it makes sense, considering the campuses are about five hours apart – an hour closer than Ole Miss (Oxford) , the second-closest SEC campus to Fayetteville.

“I believe in the next decade or so it will be a good rivalry,” former Arkansas quarterback Matt Jones says. “Both Arkansas and Mizzou are kind of in the same boat” in terms of overall recent football success. For the hate to really to flourish, though, Missouri must remain near the top of the SEC East and Arkansas must start beating its SEC West foes. He believes that for a true rivalry to flourish between two SEC programs, they must both meet in a regular season finale, both should win roughly half the games they play with each other overall, and each program should – at least once every five years – play in the game with an SEC Championship Game appearance on the line.

It’s possible if both teams head into that final game with zero or one loss, they would meet again a few weeks later in the SEC Championship Game. That’s something LSU and Arkansas can’t do now. And it’s not inconceivable that if both programs keep building off their current momentum, they may in a few years end up as two of the four (or eight) College Football Playoff teams. Any post-season clash at this level would kick the rivalry authentication process into warp speed.

Mutual success in the early years will ensure a healthy rivalry in the long run even when both programs inevitably wane at some point. Matt Jones likened this dynamic to Ole Miss and Mississippi State, where “if they beat each other and nobody else, that’s all that matters. It was never like that with LSU and us.”

Two other important factors here: A) As an SEC newcomer, Missouri hasn’t yet had time to develop a more hated in-conference rival already as Texas and LSU had and B) The rivalry’s basketball side will complement and strengthen the football animosity in ways that never happened with LSU-Arkansas or even Texas-Arkansas.

The fact left Hog basketball coach Mike Anderson and much of his staff left Missouri for Arkansas plays a lot into this, of course. It also helps the states of Missouri and Arkansas are in golden eras in terms of elite basketball recruits per capita, their schools often recruit against each other for the best players and that in vast swaths of northern Arkansas and Missouri, basketball – not football – is the most popular sport. That’s not the case in Louisiana and Texas.

Time will tell exactly what form the Missouri-Arkansas rivalry takes, and how deeply it will impress itself on the memories and hearts of today’s young Arkansans and Missourians.

In the short term, however, we have a much more concrete image of what the rivalry will look like. Earlier this month, the two colleges announced the game’s logo:

In a press release, the University of Arkansas played up the “geographic and historical boundaries” between the states, “from disputed demarcations of the border separating the two states to notable alumni and former personnel with ties to both storied athletic programs. The historic rivalry between the two states will take on even more meaning now, as every Thanksgiving weekend the Battle Line will be drawn on the gridiron. The Razorbacks or Tigers will ultimately stake claim to the “Line” – until the next meeting.”

We don’t yet know what the “Line” is, exactly, but don’t be surprised to see a trophy emerge here. Will it, like the Golden Boot, be clad in the glory of a thousand suns?

Probably not.

But there are some interesting ideas out there. I find it hard not to like the message board favorite “ARMOgedden,” but for now the graphic representation of it wallows in alumni association tailgating motif purgatory.

Former Arkansas quarterback Matt Jones would like to see a kid-friendly trophy emphasizing the mascots. It would represent a giant pot, containing a “Tiger Sooey” witches’ brew that would be stirred by some not-yet-defined creature’s hand, he says. Perhaps sticking out from the pot would be a tiger paw, or hog’s leg. Perhaps a witch looking like a hog-tiger hybrid stirs it. Suffice to say, Jones’ idea hasn’t exactly congealed.

David Bazzel has also had a crack at it. His idea is one Carmen Sandiego would love. The logo he designed features the line of latitude which serves as much of Arkansas’ northern border. Nationally, the parallel 36°30′ north is best known for marking the Missouri Compromise, which in the early 1800s divided prospective free and slave states west of the Mississippi River:

For a few years controversy extending all the way to Washington D.C. entangled the Missouri-Arkansas area near the Mississippi River. The result: Arkansas’ weird, jagged northeastern corner. “I think anything’s cool if you have a historical context to it,” Bazzel says. If his idea had taken, “people would have said ‘What is 36°30’?’, and that’s where you would have to explain it to them. So it would have included history.”

Bazzel says he offered his concept to some people at IMG College, a major collegiate sports marketing company, involved creating the rivalry logo. He isn’t sure to what extent, if any, his idea was assimilated into the final rendition. “I don’t mind the ‘battle line,’” he says. “It’s similar to what I was doing.”

When it comes to branding the future of Arkansas and Missouri’s rivalry, the past is in.

Houston Nutt Predicts Arkansas Will Beat LSU, Make Bowl Game

Posted: November 13, 2014 Filed under: College Football, Razorback football, SEC Football Leave a commentTemperatures during this Saturday’s game between Arkansas and No. 20 LSU may dip below freezing, but when it comes to competitiveness no SEC trophy game series has been hotter. In each of the last nine games of this rivalry, an average of 6.2 points has been all that separates the teams. Eight times the difference has been eight points or less. It appears the only other major college trophy series with more consistently exciting finishes has been Duke-North Carolina, decided by an average of five points* in the same span.

In the last three years, LSU’s and Arkansas’ fortunes have fallen — the Tigers’ a little, Hogs’ a lot — but the two sides haven’t let their fans down when facing each other. In 2012, nobody thought the burning Hogmobile soon-to-be-fired coach John L. Smith drove into Razorback Reynolds Stadium could pull away with a win against No. 8 LSU, but those struggling Hogs somehow out-gained LSU 462-306 in total yardage and in the closing seconds were an 18-yard touchdown pass away from forcing overtime.

Likewise, last year’s game also came down to the last couple minutes, when LSU quarterback Anthony Jennings found receiver Travin Dural on a 49-yard TD bomb that detonated Arkansas’ hopes of picking up a first SEC win since 2012.

Arkansas (4-5, 0-5) still seeks that first landmark victory. Many insiders predict the Razorbacks get it Saturday night at home. Coming off a strong showing against No. 1 Mississippi State and a bye week, Arkansas is favored by 2, according to the latest NCAAF game lines. This likely marks the first time a college football team without a conference win is favored over a Top 25 opponent this late in the season.**

Louisiana State, the would-be victim, looks to rebound from a bruising home loss to Alabama. Jennings was banged up in in the 20-13 affair and projects to have limited mobility against an Arkansas defense among the nation’s best in creating havoc in its opponent’s backfield. “Arkansas couldn’t catch them at a better time,”says Houston Nutt, former Razorback head coach. “You have a team who fought their guts out against Alabama … and now they have got to come to Fayetteville against a very hungry Arkansas team.”

“You know [LSU] is used to fighting for championships as well,” he adds, noting the difficulty of physically recovering from last week’s slugfest and overcoming a natural emotional letdown after losing an SEC West title shot. “They’re probably out of it.” Nutt predicts Arkansas will not only beat LSU, but ultimately go to a bowl game after winning at least one of its following two games against Ole Miss and Missouri.

Any bowl is great news for an Arkansas program starving for success. The same cannot be said of LSU, which was so close to still being in the hunt for a College Football Playoff berth. Now, whether it finishes the season with seven or nine wins, the Tigers are likely returning to the Outback Bowl or to the Taxslayer, Belk, Liberty, Texas or Music City bowls, writes The Advocate’s Scott Rabalais. Not exactly music to Tiger fans’ ears.

Given what’s not at stake, it’s time Les Miles and the LSU staff maximize the develop of their record 17 true freshmen these next three games, Rabalais says. Split quarterbacking duties between the struggling Jennings and frosh Brandon Harris. Crank up the carry-o-meter for freshmen tailbacks Leonard Fournette and Darrel Williams. And “maximize the D-line rotations for the younger players like Sione Teuhema, Frank Herron, Greg Gilmore and Maquedius Bain. In the secondary, get more work for youngsters like Ed Paris and Jamal Adams and Russell Gage.”

“This season was never going to be about championships,” Rabalais adds. “It was always going to be a bridge to what the Tigers hope will be a brighter future.”

Paradoxically, this kind of talk, as well as the betting lines, may actually serve as a greater incentive to LSU players than whatever on-field consequences an Arkansas win could mean for them. Yes, of course, they want to keep the nearly 200-pound Golden Boot on campus for the fourth straight season. And what erstwhile SEC champion wouldn’t prefer a return trip to sunny Tampa to the prospect of a 56th AutoZone Liberty Bowl in Memphis?

But despite what players and coaches say in public, simple pride and retaliation for a perceived slight can sometimes be the powerful motivation of all. In public, it’s foolish for coaches to admit they pay attention to Vegas and all the media chatter. But in the privacy of their locker room, it’s smart to use any perceived disrespect as extra fuel for competitive engines that may be running on low.

LSU won’t become Arkansas’ first SEC victim of the Bret Bielema era without a nasty fight. Expect another classic finish in the conference’s most heart-stopping rivalry.

Evin’s Scale of SEC Trophy Game One-Sidededness

Before 2014*, there were five trophies circulating in and among the sweaty, intraconference climes of SEC football country. Each one represents a decades-old rivalry, with LSU-Arkansas the baby of the bunch. What their Golden Boot lacks in tradition, though, has more than been made up for in sheer entertainment value. The below scale, based on final score differences, ranks the SEC trophy rivalries on a scale from most consistently entertaining (1) to most likely to cause a re-reading of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter for lack of anything better to do (5). Winners are in parentheses.

1. LSU-Arkansas (Golden Boot)

| Year | Point Differential |

| 2013 | 4 (LSU) |

| 2012 | 7 (LSU) |

| 2011 | 24 (LSU) |

| 2010 | 8 (UA) |

| 2009 | 3 (LSU) |

| 2008 | 1 (UA) |

| 2007 | 2 (UA) |

| 2006 | 5 (LSU) |

| 2005 | 2 (LSU) |

Total Point Differential: 56

Per-Game Average: 6.2

2. LSU/Ole Miss (Magnolia Bowl)

| Year | Point Differential |

| 2014 | 3 (LSU) |

| 2013 | 3 (Ole Miss) |

| 2012 | 6 (LSU) |

| 2011 | 49 (LSU) |

| 2010 | 7 (LSU) |

| 2009 | 2 (Ole Miss) |

| 2008 | 17 (Ole Miss) |

| 2007 | 17 (LSU) |

| 2006 | 3 (LSU) |

Total Point Differential: 90

Per-Game Average: 10

3. Florida/Georgia (Okefenokee Oar)

| Year | Point Differential |

| 2014 | 18 (UF) |

| 2013 | 3 (UG) |

| 2012 | 8 (UG) |

| 2011 | 4 (UG) |

| 2010 | 3 (UF) |

| 2009 | 24 (UF) |

| 2008 | 39 (UF) |

| 2007 | 12 (UG) |

| 2006 | 7 (UF) |

Total Point Differential: 118

Per-Game Average: 13.1

4. Ole Miss/Mississippi State (Golden Egg)

| Year | Point Differential |

| 2013 | 7 (MSU) |

| 2012 | 17 (Ole Miss) |

| 2011 | 28 (MSU) |

| 2010 | 8 (MSU) |

| 2009 | 14 (MSU) |

| 2008 | 45 (Ole Miss) |

| 2007 | 3 (MSU) |

| 2006 | 3 (Ole Miss) |

| 2005 | 16 (MSU) |

Total Point Differential: 138

Per-Game Average: 15.3

5. Alabama/Auburn** (Foy-ODK Sportsmanship Trophy)

| Year | Point Differential |

| 2013 | 6 (AU) |

| 2012 | 49 (UA) |

| 2011 | 28 (UA) |

| 2010 | 1 (AU) |

| 2009 | 5 (UA) |

| 2008 | 36 (UA) |

| 2007 | 7 (AU) |

| 2006 | 7 (AU) |

| 2005 | 10 (AU) |

Total Point Differential: 149

Per-Game Average: 16.6

*The new Texas A&M-South Carolina and Missouri-South Carolina series involve trophies, too. Which is nice. But for membership in this particular club, you need to have been clashin’ man horns for at least nine years running.

** Yes, the 2010 and 2013 Iron Bowls were awesomely entertaining. But Crimson Tide routs in 2008, 2011 and 2012 have made the series’ games on the whole the least consistently compelling.