Who is the Best in the West?

Posted: July 7, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentWho has the odds in their favor?

In the Western Conference, there are only two teams, the Timberwolves, and Warriors, that are officially eliminated from the newly reconfigured playoffs. It has been a stunning reversal of fortune for Golden State after five consecutive conference crowns and three world titles over a five-year span that came to a screeching halt in 2020.

But the Warriors’ precipitous fall from grace is a story for another day because we must now focus on the here and now. Los Angeles is the favorite to win the West and the odds on the Lakers are +130 to do so, followed closely behind by their crosstown rivals, the LA Clippers at +200. Let’s see what the oddsmakers are dealing on the 13 teams still remaining in the Western Conference playoff hunt.

Los Angeles Lakers +130

Los Angeles Clippers +200

Houston Rockets +650

Denver Nuggets +1500

Dallas Mavericks +2000

Utah Jazz +2200

New Orleans Pelicans +5000

Oklahoma City Thunder +5000

Portland Trail Blazers +6600

Memphis Grizzlies +10000

San Antonio Spurs +30000

Sacramento Kings +50000

Phoenix Suns +75000

The Contenders

This is a peculiar season for obvious reasons and when world-class athletes get their routines disrupted, strange things happen. Take for example the resumption of the PGA Tour in Fort Worth, Texas just a few weeks ago. The Colonial Country Club was ground zero for the Charles Schwab Challenge, and a crowded field of 148 players descended on the first tournament held since the COVID-19 pandemic halted play, back in March. Although Tiger Woods decided to skip the CSC, there was still plenty of star power at an event that is not normally known to attract so many top guns.

When the dust settled it was not the No. 1 golfer in the world, Rory McIlroy, or any of the favorites like Jon Rahm, Justin Thomas, Brooks Koepka, or Dustin Johnson who won the day but rather a 60-1 long shot named Daniel Berger who defeated a 40-1 entry named Collin Morikawa in a playoff round.

And while basketball and golf are worlds apart, it is important to note that upsets are far more likely to occur when professional athletes get taken out of their routines, which can allow lesser talents a window of opportunity. Let’s also not forget that the teams are coming in cold, with no momentum to build on and little time to rekindle the magic.

As good as the Lakers have been this season, owning a .778 winning percentage trailing only the Milwaukee Bucks, every team falls into a funk just as LA did during a four-game losing streak from December 17th through the 25th. But that’s not a big deal in the middle of the season but if it happens when teams are still shaking off the rust in the unfamiliar environs of Walt Disney World, then we could see a few dragons slain when the playoffs begin.

The Denver Nuggets are the most likely to be dubbed the Cinderella story of this unusual 2020 postseason as they have enough talent on their roster to stun even the best in the business. Twenty-three-year-old Jamal Murray was getting better as the season wore on and he will be the gamechanger if the Nuggets get hot.

However, the talented triumvirate of the Lakers, Clippers, and Rockets are the best in the West, and although many believe this is merely a coronation for LeBron, AD, and the Lakers it would be foolhardy to discount the Clippers. Kawhi Leonard spurned all other offers to make history in bringing a championship to the other LA basketball franchise and working alongside the talented Paul George.

Leonard already has two championships under his belt, as a member of the Spurs and Raptors, and understands a lucky bounce, a fortuitous call, and a healthy roster can get a team to the Promised Land, “I just think if we keep doing that, we can be successful, but it always doesn’t work to your favor. It’s a lot of luck in it — calls, making shots, people staying healthy. I think we just have to keep moving on the right track and staying positive.”

As good as LeBron is, he is past his prime while Kawhi Leonard is in his physical peak. The public is squarely on the Lakers but the smart money says the Clippers win the West!

“African-American Athletes in Arkansas” & the AR Sports Hall of Fame

Posted: April 6, 2018 Filed under: Sports Sears Leave a commentCome visit Evin Demirel, author of “African-American Athletes in Arkansas,” before and during the Induction Banquet of the 2018 Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. He will sell first edition copies and collectible posters of his groundbreaking book, which Ronnie Brewer endorsed as:

“Really well written, informative stories about the Arkansas greats and people who paved the way for my dad, Almer Lee, Martin Terry and others.… It will speak to athletes, coaches and history lovers across the state and region.”

The groundbreaking anthology features stories on past ASHOF inductees like:

-

Former Razorback coach Fred Thomsen, who promoted and oversaw scrimmages between the white Fayetteville Bulldogs and “Black Razorbacks” in the 1930s.

-

“Dizzy” Dean, whose long standing rivalry/friendship with Satchel Paige broke down racial barriers in the Great Depression.

-

“Goose” Tatum, who teamed with Lonoke County native “Sweetwater” Clifton, the first African American to sign with and play for the same NBA team.

-

Eddie Miles, an eventual No. 4 NBA draft pick whose superstardom at the all-black NLR Scipio Jones High compelled UA basketball coach Glen Rose to make him that program’s first black recruit.

… and many more.

Watch interviews with Demirel, a former Democrat-Gazette reporter, on KATV and

“Sports teaches so much about life—giving your best, the power of a team, unity and love. I wish America could live that way. I hope many more get to read this refreshing journey…. it’s a book every sports fan in Arkansas should read.”

— Ken Hatfield

“It brought back memories of growing up in a predominantly black neighborhood and the Arkansas School for the Deaf where my parents taught skin color blindness for 34 years. A really good read about African-American men, like my coach Eddie Boone, who journeyed through the state’s history and some of the steps they had to take for the next generation.”

— Houston Nutt

“If you are a sports fan, it is a great read. If you are into Arkansas sports history, it is a great read.”

— Wally Hall

***

Talking with NBA Finals MVP Andre Iguodala In Istanbul

Posted: June 15, 2015 Filed under: Pro basketball, Razorback basketball | Tags: Allen Iverson, Andre Iguodala, Besiktas, Cedric Maxwell, Golden State championship gear, LeBron James, Melvin Watkins, NBA Finals MVP, Nolan Ricahrdson, Steph Curry, Warriors championship T-shirt, Warriors title T-shirt Leave a commentJune 16, 2015 UPDATE

It’s official. Afterward, he discussed becoming the first MVP to not start a single game preceding the Finals: “We all say God has a way for you, a purpose for you, and I accepted it.”

In fall of 2010, fans of the Turkish basketball club Besiktas welcomed through the doors of their home arena the most famous “AI” in American team sports – the one and only Allen Iverson. While Iverson’s tenure in Istanbul only lasted 10 games, his late-career stint abroad generated significant headlines across the world.

Just months before, though, another “AI” sat in the bleachers of Besiktas’ home arena. This AI, Andrew Iguadala, had been teammates with Iverson on the Philadephia 76ers and was forever battling the moniker of, well, “the other AI.” Although a first rate talent, Iguadala was in many fans’ minds a perpetual afterthought, an All-Star without any identifiable All-Star skill or trait beyond sheer hustle, defense and court smarts.

In August 2010, I was in Istanbul to report on the FIBA World Championships and thanks to the help of fellow writers like Brian  Mahoney and Chris Sheridan, I found myself in Besiktas Arena during a Team USA practice to do interviews for the Associated Press and other outlets. After leaving a horde of TV cameramen buzzing around Kevin Durant and Derrick Rose, I noticed Iguodala in the stands by himself, reading.

Mahoney and Chris Sheridan, I found myself in Besiktas Arena during a Team USA practice to do interviews for the Associated Press and other outlets. After leaving a horde of TV cameramen buzzing around Kevin Durant and Derrick Rose, I noticed Iguodala in the stands by himself, reading.

I introduced myself as a writer. He studied me for a second, and soon asked where I was from.

“Arkansas,” I replied. Iguodala’s eyes lit up. “I was going to go there,” he said, and he briefly explained he’d signed a national letter of intent with the Razorbacks before Nolan Richardson was fired and Iguodala decided to go to Arizona instead.

That connection seemed to loosen Iguodala up a bit and I then asked him about the book he was reading. He showed me the cover of “The Alchemist” and told me it was about a young man’s personal journey in search of his “Personal Legend,” and went in to what that meant. Admittedly, it’s pretty mystic but boils down to “something you have always wanted to accomplish.” Like tens of millions of others, it was clear the book’s author Paulo Coehlo had captivated Iguodala with the notion that each of us have a quest, a calling and, in the end, a kind of destiny to fulfill.

***

Fast forward five years and it appears Iguodala may be on the brink of fulfilling his own “Personal Legend.”

In these NBA Finals, the 6’7″ small forward has arguably been the most important player on the court for Golden State. The longtime “other AI” is at last becoming “the AI” despite in the regular season playing off the bench for the first time ad averaging career lows in points, rebounds and assists. Yet in Golden State’s first three games, when the Warriors needed it most, it was Iguodala among all the Warriors who played with the most passion, pace and confidence. Most importantly, he has played the strongest individual defense on LeBron James and that defense has been a big part in James’ breaking down at the end of the last two games.

Iguodala’s significance in the Warriors’ title run was never more explicit than last week when Golden State, which had been heavily favored entering the series according to sportsbook online betting, fell down 2-1. Searching for a jolt, Warriors head coach Steve Kerr inserted Iguodala as the starter in place of Harrison Barnes. The move has ignited two straight wins and a flood of meme-y Iguodala highlights:

With regular season MVP Steph Curry getting off to an historically bad Finals start, it was Iguodala more than any other Warriors player who stood as the team’s top MVP candidate following Game 4. An NBA Finals MVP for him would be historically notable and precedent-breaking in many ways. Here are a few:

1) Iguodala

would beis the first Finals MVP on the same team as a healthy regular season MVP. Yes, Magic Johnson did win it as a rookie in 1980 during the same season his teammate Kareem Abdul-Jabbar got MVP honors. But Abdul-Jabbar suffered an injury late in that series against Philadelphia, clearing the path for Johnson – a point guard, mind you – to step in at center with a Game 6 magnum opus that to this day staggers the mind.2. Iggy

would beis the first Finals MVP since Wes Unseld in 1978 to average less than 10 points a game in the regular season. (Even Celtic Cedric Maxwell, who was nicknamed “Cornbread” by Arkansas assistant coach Melvin Watkins, averaged 15 points a game before stealing thunder from a young Larry Bird to win the 1981 Finals MVP)3. He

would beis the first Finals MVP who did not start a single game during the regular season.4. He

would bemay be the first Finals MVP who didn’t finish at No. 1 or No. 2 on his team in points, assists, blocks, rebounds and steals during a championships series (Currently, he ranks at No. 3 in all those categories for the Warriors – a testament to his versatility).

In the end, it’s likely the man at the top of a few of those rankings – Steph Curry – will continue to shoot lights out as he did in Game 5 and secure Finals MVP honors if Golden State wins the series. And it’s likely, after a brief turn in the limelight, Iguodala will go back to being an afterthought in the minds of many NBA fans.

But no matter what happens, the Springfield, Ill. native’s series-altering energy, hustle and savvy in these Finals shouldn’t be forgotten.

Years from now, expect his play these last few games to be central to the legend he is building.

Commemorate the Warriors’ historic run with this one-a-kind design:

“Their Joy was Unrestricted” – When State Prisoners Played Pro Baseball Players

Posted: June 10, 2015 Filed under: Baseball | Tags: baseball inmates, Marin County baseball, prisoners in sports, San Quentin Leave a commentThis is a fascinating post which will make you consider a new definition for “free agent.” It looks at a group of pro baseball players who locked horns with California state prison inmates called “the Midgets.”

Unfortunately, not many details could be released about who these prisoners were. But we do know prisoners No. 27784 and No. 26130 had some serious skills…

After Charles “Cy” Swain lost his leg in an accident after the 1914 season, he attempted to stay active in baseball by forming a team called the Independents with another former player, Tommy Sheehan.

Swain managed the team which was comprised of minor and major leaguers who spent the off-season on the West Coast.

In the early spring of 1916 the team played their most unusual game. The San Francisco Chronicle described the scene:

“For the first time in the history of the State Prison across the bay in Marin County, the convict baseballers were yesterday permitted to play against an outside team…The attendance? Good! Something like 2300 men and women prisoners, even including the fellows from solitary confinement, took their seats to watch the game, and their joy was unrestricted.”

Swain’s Independents were playing the Midgets, the baseball team at San Quentin.

The paper said Swain…

View original post 228 more words

Will Hogs Join Duke, Ohio State & Arizona State to Hit Rare “Player of the Year” Trifecta?

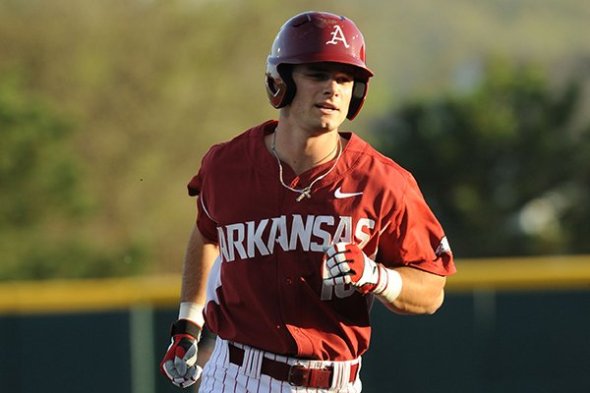

Posted: May 21, 2015 Filed under: Baseball, Razorback basketball, Razorback football, SEC Football | Tags: Andrew Benintendi, Arkansas Razorbacks baseball, player of the year 2 Comments One opposing SEC coach called Andrew Benintendi the nation’s best college baseball player. Courtesy: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc.

One opposing SEC coach called Andrew Benintendi the nation’s best college baseball player. Courtesy: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc.

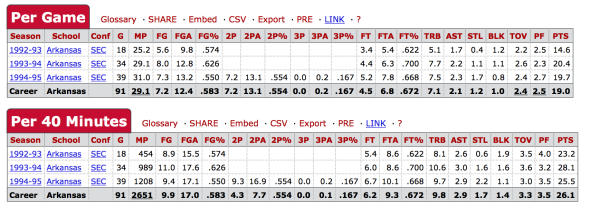

In the early 1990s, Arkansas joined the SEC and the conference began awarding a baseball player of the year award to complement already established football and basketball MVP titles. Since then, the conference has soared to lofty heights, becoming arguably the NCAA’s most powerful organization. Much of that has to do with stretches of dominance by Alabama, LSU and Florida in football; Arkansas, Kentucky, Florida in basketball and the likes of LSU (five national titles 1993-2009) and South Carolina in baseball.

Many of these programs have produced multiple players of the years in various sports, yet no one school has yet been able to hit a POY trifecta by having a male player win the ultimate individual honor in each major team sport in one calendar year.

That may soon change.

In 2015, the Razorbacks athletic department has a chance make SEC history by sweeping these honors. The push started earlier this spring with sophomore Bobby Portis winning basketball SEC Player of the Year. Then, on Monday, sophomore Andrew Benintendi was announced as SEC baseball’s player of the year. Benintendi, of course, has helped spearhead the Hogs’ surge from a 1-5 start in SEC play to 18-7 finish including two wins so far in the SEC Tournament. The outfielder from Cincinnati, Ohio leads the nation in slugging percentage (.760) and ranks first in home runs. “He’s probably the best player in college baseball right now,” Tennessee coach Dave Serrano told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s Bob Holt.

I write more about this unique record in the context of SEC sports and the Razorbacks’ upcoming football season for Sporting Life Arkansas, but here I want to look beyond the SEC.

Specifically, how many times has a school pulled off this one-year POY trifecta among all major conferences?

Three times – sort of.

Here they are:

1994 Duke

In basketball, Grant Hill secured ACC player of the year and first team All-American honors. But thanks to the Razorbacks, “national champion” was one honor he didn’t grab for the third straight year. Ryan Jackson took home ACC POY honors after setting a single-season school record with 22 home runs. In football, bruising back Robert Baldwin won it after helping lead Duke to its highest national ranking in 23 years.

Baldwin was the last Duke player to win ACC player of the year honors in football, but was the 10th such POY in school history (which is a surprisingly high number to my 33-year-old self. It reflects how un-dominant Florida State once was).

Black Razorback Fans of the Jim Crow Era: A Forgotten Past

Posted: May 13, 2015 Filed under: College Football, High School Football | Tags: Darrell Brown, first black fans, Jerry Hogan, Orville Henry, War Memorial Stadium history 1 CommentThe history of the African-American athlete at the University of Arkansas has become well chronicled in the last couple decades. Many outlets have covered their experiences on the field – ranging from Yahoo sports columnist Dan Wetzel’s look at Darrell Brown, the first black Razorback football player, to a new “Arkansas African American Sports Center” business which focuses on the histories of black student-athletes at the UA across various sports. The university’s athletic department itself has created a series honoring its minority and women trailblazers.

But what about the history of the Razorbacks’ black fans?

That story appears to be entirely unreported. It’s time that changes and – thanks to Henry Childress, Sr. and Wadie Moore, Jr. – the right time is now.

Childress, Sr., likely the oldest living African-American man in Fayetteville, told me about a small group of black men, women and children who consistently attended Razorback football games at Razorback Stadium in the 1940s. Remember – this was an era in which Jim Crow laws still pervaded the South, although the social climes of Fayetteville have always more progressive than many other Southern towns (aside from a brief flare-up of KKK activity in the early 1900s).

Childress, Sr., now in his upper 80s, recalls seeing about 25-40 black Hog fans at games he attended in the 1940s through early 1950s. They weren’t allowed to sit in the bleachers like all the white fans. Instead, they had to sit in chairs on the track which then encircled the football field. But black and white fans alike Woo-pig-sooed their hearts out during the games against Tulsa, Texas, Texas A&M and SMU which Childress, Sr. saw. A black Fayettevillian named Dave Dart was the loudest cheerleader. “He’d be out there – he’d be out on the side of the field almost. He’d be just a-holerrin’ and yelling ‘Come on!'” And soon enough, Childress couldn’t help but join the frenzy.

This Hog mania was a far cry from Childress’ younger days growing up in Ft. Smith. Then, he didn’t consider himself a Razorback or much of a football fan at all. One reason was Hogs’ games didn’t then dominate statewide airwaves like they would after 1951, when Bob Cheyne – the UA’s first publicity director – crisscrossed the state to enlist 34 radio stations in the broadcasting of Hog games.

Plus, Childress hadn’t gotten swept up in football mania at his all-black Ft. Smith high school. Lincoln High had cut its football and baseball programs by the time he moved to Fayetteville in 1944, he recalled. He added in the early 1940s the school only sponsored basketball. The teens who still yearned for football simply gathered to play it by themselves on a nearby field after classes let out. “We’d go out to the back of the school, and choose up sides.”

After moving to Fayetteville, it took a little while to warm to the fanaticism and voluminous qualities of certain Razorback fans. “It was kind of strange to me,” Childress said. “I just came out and sat and looked.” Pretty soon, though, he got the hang of it. He learned many fellow black fans actually worked on the UA campus, usually as part of house, cafeteria or groundskeeping staff. This meant they personally knew the white student-athletes for whom they rooted. Dave Dart, for instance, worked at a fraternity home and cheered on the frat bro-hogs he knew by name, Childress recalled.

Hog games weren’t the only setting where black Fayettevillians came to cheer all-white spectacles. Childress said in this era both races got off work to watch the town’s parades (which then featured all-white floats). “We’d come out and stand. There would be lines all up and down Dickson Street.”

I asked Childress what he then thought of the whole situation. Did he or any friends at any point consider it unfair only white players could represent a state university to which blacks had contributed as employees, taxpayers and students since its 1872 founding?

“No, we didn’t give it a thought,” Childress said. “Wasn’t nobody [African-American] going over there to school,” and he didn’t expect an influx of black UA students to begin any time soon.

What About Black Fans at War Memorial Stadium?

I haven’t yet found anybody who can speak to the experience of central Arkansan blacks at Razorback football games at Little Rock’s War Memorial Stadium in the immediate years after its 1947 construction.

But I did find Wadie Moore, Jr., who recalls the situation in the early 1960s Little Rock was more stratified than in 1940s Fayetteville. As a 13-year-old in 1963, Moore began working at War Memorial, where his father was a maintenance worker in the press box. Moore said about 5-10 black fans would attend each Little Rock Razorback game in that time. They didn’t sit in sight of the white fans. Instead, stadium policy “would allow you to sit under the bleachers in the north end zone and watch the game,” he said.

Wade Moore Sr.’s proximity to the media – including future local legends like Jim Bailey, Bud Campbell and Jim Elders – actually opened doors for his son, though. When Moore Jr. found a passion for sportswriting as a high schooler at Horace Mann High School, it was his father who made sure an article he wrote got into the hands of Orville Henry, the longtime sports editor of the Arkansas Gazette.

The mid to late 1960s brought a tidal wave of change to racial dynamics across the South and War Memorial was no exception. Wadie Jr. recalls one of first times he saw black Razorback fans sitting in the crowd – and not secluded below in the stands – coincided with the Little Rock homecoming of one of the Razorbacks’ first black band members. The young woman’s family, last name of “Hill” as he recalled, watched her in the audience around 1965 (the first year black UA students were allowed to live on campus) or 1966. In 1965, too, a young walk on named Darrell Brown joined the defending national champions in Fayetteville full of hope he could break down regional color barriers all by himself. By the end of the next fall he would limp away, that hope beaten out of him.

But he had opened the doors for others, including Jon Richardson – who a few years later became the Hogs’ first black scholarship player.

In 1968 one of Richardson’s schoolmates, Wadie Moore, Jr. became the first black sportswriter at Arkansas’ oldest and most prestigious statewide newspaper.

There are hundreds of other stories about Arkansas’ forgotten sports heritage which need to be recorded and published before it’s too late. Thank you to Henry Childress, Jr., Rita Childress, Jerry Hogan (author of the NWA pro baseball history Angels in the Ozarks) and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History) for helping me find a treasure of historical knowledge in Henry Childress, Sr. Send tips on stories/interviewees to evindemirel [at] gmail.com.

For more on this topic, visit my other work here:

1. Vanishing Act: What Happened to Black Baseball in Arkansas? (via Arkansas Democrat-Gazette)

2. Integrate the Record Books (via Slate)

3. It’s Time Arkansas Follows Texas in Honoring its Black Sports Heritage (via The Sports Seer)

Bobby Portis Channels Trey Songz In Farewell Press Conference

Posted: April 15, 2015 Filed under: Pro basketball, Razorback basketball | Tags: Bobby Portis, Hall High School, Mike Anderson, Trey Songz, trey thompson 1 CommentBobby Portis doesn’t have much hair.

But what little he has, he let down in full during a Tuesday press conference after announcing he was taking his game to the next level. In basketball, he’s a potential lottery pick. In singing, he’d be lucky to find volunteer work in Bulgaria. Below is the full conference transcript. Excerpted video of Portis’ serenade is near the middle.

Mike Anderson: This is a day that, you know, you have dreams when you’re a young kid. Coming here, taking this job four years ago, one of the first tasks that I had was to go down to Hall High School, and see this young man work out. In that spring, in that summer, this committed to the University of Arkansas. His sophomore, you’re talking about finishing his sophomore year, so when you talk about a guy committed early, this guy committed early, so to sit here four years after that, and he has an opportunity to realize his dream. It’s kind of a more sweet than it is bitter day. Why, because this kid, he’s part of my family, and that’s Bobby Portis, as well as all my other players on our team. When you talk about a young man who’s had two unbelievable years, it’s amazing what has taken place. In his freshman year, he’s second team All SEC. His second year. You got to understand this. He’s second team All-American. That is a special, special year, and that’s why we are here today.

His teammates are here in attendance, as well as our staff, as Bobby has announced that he will be moving beyond that, and I’ll let him talk more into that. As a coach, he’s been a great ambassador for our university. He’s a great basketball player, we know that, but he’s been a great, great ambassador, a great, great role model for a lot of young players around, young people in the state of Arkansas and around the country. We could not have a better representative than Bobby Portis. To be here today as he makes his statement, I couldn’t be no more proud of Bobby Portis. Player of the year in our league. Things that haven’t taken place here in 20 years. That tells you how special he is. Not only special Bobby is, but his teammates as well. He’ll be the first to say that. I can’t talk any more, because I get a little emotion, but to Ms. Tina, I want to thank her for entrusting me with her son. I told her, “You send me a young boy, I send you back a man.” Well, he kind of expedited the process. I told him to go at his own pace, as a freshman, because coming in, you can imagine, McDonald’s All-American, all the pressures, and I said go at your own pace. His pace was a tremendous pace, and that’s why we’re here today. I just pass over here to Bobby Portis.

Bobby Portis: How everybody doing today? Ain’t nobody sad or nothing, is it? Everybody good? You know, today’s a good day

for me, to try to take that next step and go to the NBA. As a kid, all kids grow up wanting to go to the NBA. For me, myself, I finally had that first chance to go to the NBA this year, so I took the opportunity and tried to run with it. Thanks for Coach A for always having that trust in me, on and off the court. He made me a captain this year, as a sophomore, and I think that’s big for me and my teammates. Thanks for my teammates, always having their trust in me, on the court, passing the ball to me, even though I’m hollering, “Give me the ball! Give me the ball!” All that stuff. Thanks to Coach [Matt Zimmerman] staying late in the gym with me, and always rebounding for me and all that. Thanks to the managers, too, and Coach Watkins and Coach Cleveland. You’re all a part of my family, now, and this is something that I’m proud of, so thank you all and God Bless.

Reporter: You really talked a lot about your mom and what she means to you. How big a part was her, how hard she works and what she does, in your decision?

Bobby Portis: It was a big part, just because, my mom, she works 2:00 AM to 1:00 PM. That’s an 11 hour shift. For any person, that’s a tough burden on anyone, so I just want to take that next step, not just for her, but for myself. I’m not doing this for my mom, or anything, I’m doing this for Bobby Portis, just because I feel like I’m ready to take that next step, and go on about my basketball career.

Reporter: In the beginning you said it was going to be a committee decision. In the end, was it just you that made the call?

Bobby Portis: I believe so, just because, my mom wanted me to make the decision for me and not her. That’s something that she always preaches. Not trying to make me make a decision for her, just to change her life and my little brother’s life. She wants me to live my dream and try to be the best basketball player I could be.

Q: I understand it’s a basketball on one side, but how nice is it that you’re going to be able to help your family out?

Bobby Portis: I think it’ll be nice to help my family out, but I still have to work as hard as I can every day, and just try to be that same person that I was, and just stay humble and hungry. Just because, if I get my name called and put that hat on, that doesn’t mean that it’s just the end of the road and I get money. It’s more than just money. It’s a job, too, at the same time.

Q: What kind of feedback did you get from the NBA folks about where Bobby’s likely to be drafted?

Mike Anderson: First of all, this wasn’t an easy decision for Bobby. This guy, again, he committed as a sophomore to be a Razorback, and trust me, he’s been wrestling with this. I know you guys, whether it be social network, or we continued at the banquet last night, “Hey, Bobby, what you going to do?” It wasn’t an easy decision for him, so we gathered information for him, in terms, of where, what’s going to take place. Obviously, from the lottery to first round. He’s going to be … He’ll be a first rounder, there’s no question about it. Where? That remains to be seen. I have all the confidence in this guy, right here. He’s on the fast track, on the fast track to do some great things. No one can knock his work ethic. For a 6’11” guy, that can do the things that this guy does, is remarkable. He has that burning desire, to not only be a good player, so even as he goes to that next level, he don’t just want to be a good player in the NBA, he wants to be a great player in the NBA. I don’t question anything this guy puts his mind to. The feedback we got was very positive, and so we sat down, and just discussed it. At the end of the day, it was Bobby’s decision, and I think, one thing about it is that, I think, for him, I think he made the right decision.

He’s done some great things here for us, here at the University. Took us some places we hadn’t been in a while. I think he just starting something that’s really going to continue to take place, and when you talk about elite players, having the opportunity to come in, and have a chance to showcase the God gifted talents. He took my word, when I sat there with he and his mom, because there’s a lot of places he could have went. There’s a lot of programs he could have went. He chose the University of Arkansas. In the matter of a year, two years, now he’s had an opportunity to go and live his dream. It’s a big statement in a lot of ways. I’m sure the basketball people out there, the NBA teams, and hopefully, the recruits understand that, you know what – we get it done here at the University of Arkansas. Our kids, they develop. They do it the right way on and off the floor and when they leave here they will be ready, not only for the NBA, but they will be ready for the real world.

Q: What was the tipping point when you decided everything?

Bobby: Last Tuesday me and Coach Anderson sat down and talked about everything. He just laid out two or three scenarios and from there, I kind of ran with it. I sat down and told him then that I thought I was ready to make that next step. I made it last Tuesday.

Q: … How tough a decision was it? … Like Mike said, it was something you had to wrestle with.

Bobby: Man, last night I played this song, “I don’t want to leave, but I got to go right now.” That was cold, though. No, it was a tough decision for me just because growing up in the state of Arkansas and being a native of this state, I felt like I was a great ambassador for our basketball team and for our program, not only for the basketball team, but for the whole, entire Razorbacks. I believe I showed kids that you don’t have to go to Kentucky or Florida just to try to live your dreams. Coach Anderson and his staff gets it done here, too.

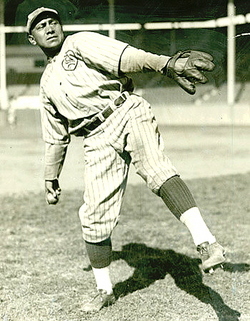

Upcoming Movie about Arkansas Traveler Legend / Native American MLB Pioneer Mose YellowHorse

Posted: April 4, 2015 Filed under: Baseball | Tags: Arkansas Travelers, Indians in MLB, Mose Yellow Horse, Mose YellowHorse, Native Americans in Baseball, Pittsburgh Pirates Leave a commentA film production company has optioned the rights to a screenplay about Mose J. YellowHorse, a star on the Arkansas Travelers’ first championship team and the first full-blooded Native American in the MLB. Enid, Okla.-based River Rock Entertainment will work with screenwriters Todd Fuller and his wife on developing the script after their first draft is finished, according to Fuller.

YellowHorse was not the first Native American in the big leagues, nor the best, but was certainly one of the most colorful. As a child growing up Pawnee, Okla., he performed as a child in the Pawnee Bill Wild West Show and, according to the story of his relative, Albin LeadingFox, learned how to throw a baseball by hunting rabbits and birds with rocks. His fastball became elite.

In 1920, he led the Arkansas Travelers, then in the Southern Association, to their first league championship. The team went 21-7 and included included Joe Guyon, who in football had starred in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s backfield with Jim Thorpe and Bing Miller, who went on to post a .316 lifetime batting average in sixteen major league seasons, according to Fuller’s “60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse.” The screenplay will be an adaption of this book.

YellowHorse then spent a couple of seasons in Pittsburgh, where his roaring fastball and gregarious personality made him a kind of cult figure for decades afterward. His final career tally was eight wins, four losses and 3.93 ERA in 126 innings, but his most memorable stat might have been a purposefully mis-hurled foul thrown at Ty Cobb, one of the greatest players of the early 20th century.

Fuller relays the story from an interview he conducted in 1992 with one of YellowHorse’s friends:

“Ty Cobb was crowding the plate anyway, he always did. And Mose wasn’t going to let him get away with it. Cobb was up there yelling all kinds of Indian prejudice, real mean slurs at Mose, just making him mad anyway. So he shakes off four pitches until the catcher gives him the fast ball sign, and Mose nods his head. I mean everyone in Detroit was whooping and all that silliness. So he winds up and fires the ball as hard as he could, and he knocked Cobb right in the head, right between the eyes. Mose knocked him cold. And a fight nearly broke out at home plate. All the Tigers’ players came rushing off the bench. The Pirate players started running toward Mose. But no punches were thrown. They just carried Ty Cobb off the field. And all three of the Pirates’ outfielders just stood together in center and laughed. Said they wished they could see it again.”

The incident is notable as a reversal of the common narrative often framing the relations of Indians and Anglo-Americans in this era. Here, it is a full-blooded Pawnee “who holds the weapon (a ninety-five mile-an-hour fastball) and inflicts harm,” Fuller writes. It’s also significant YellowHorse’s teammates eagerly enter a fracas to protect him, suggesting a loyalty and camaraderie that would prove so instrumental in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ success with Jackie Robinson a quarter century later.

When reading this, I couldn’t help but think of the similarities here between YellowHorses’ actions and those of one of the “Jackie Robinsons of the NBA” – Arkansas native Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton. In the early 1950s. Clifton had no quibbles about flattening those who would spew racist vile at him. Instead of throwing baseballs, though, the 6-7 center threw enormous fists at the faces of offenders.

The rest of YellowHorse’s life is one of sadness (alcohol addiction) but ultimate redemption found in his homeland. His story, like those of other minority baseball pioneers, is an important one. Godspeed to those who would make a movie about it.

I’ll leave with the following poem intro. The scene is Pittsburgh, 1921, in the moments before Moses’ major league debut:

What it Means to Wear #50 (for the Pittsburgh Pirates)

This moment begins in the dim light

Of a locker room, and Mose Yellow-

Horse struggling against his uniformButtons. It’s just y’r nerves the boys

Tell him, but he knows it’s butterflies

And the sparkle of Opening Day.Soon enough he’ll take in the field,

The crowd of twenty-five thousand,

See mustard dripping from the chins

Of enchanted fathers.This will be the first time they’ve seen

An Indian in Pittsburgh. And some

Whoop and holler; mumble & inquire.Some will cheer. They watch the Reds

And Pirates battle deep into the tussle;

Nip and tuck from the start.It’s April 21, and Mose YellowHorse

Doesn’t know that kids are peeking

Through cracks in the outfield wall…

Read the rest of this Todd Fuller poem here.